From the Editor

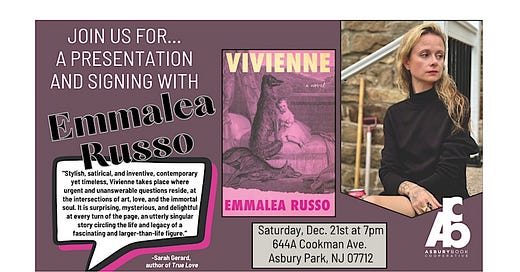

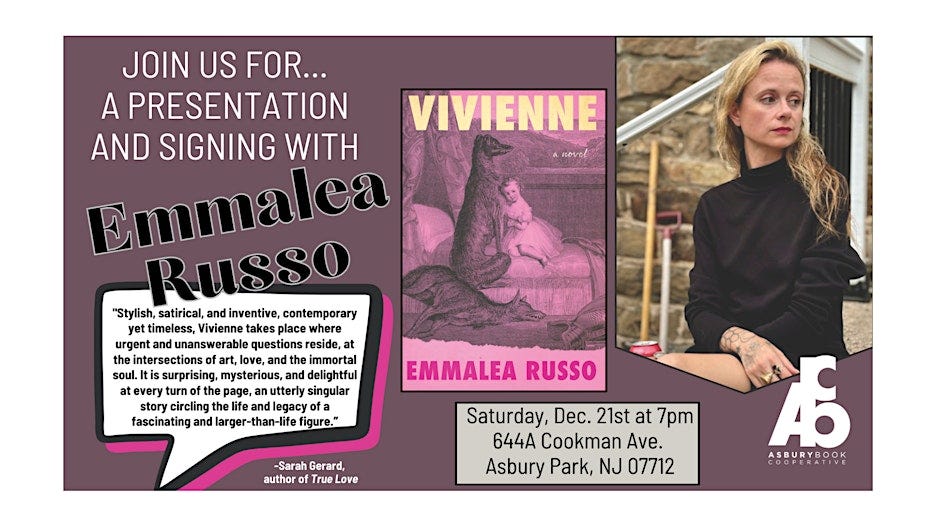

Leading up to an exciting evening with Emmalea Russo, we want to take some time to celebrate Vivienne. Much of the novel takes place during this very week. So, starting with “December 16,” we will share snippets of a few days as they happen in the novel—so we can experience this week alongside Emmalea’s characters—leading up to Emmalea’s event on December 21st (which is also the penultimate section and final day in the novel). Make an appearance, and Emmalea will sign your copy of Vivienne after a presentation in the surreal style of the novel.

If you like what you see here (we know you will), go ahead and buy the book, enrich your week by immersing yourself in the strange and surreal experiences of Vivienne et al., then take the book to Asbury Book Cooperative at 644A Cookman Ave. in Asbury Park, NJ, on Saturday to have its wonderful creator sign it for you. (You can, of course, buy a copy at the event as well). Be sure to reserve your spot here.

In the meantime, here is “December 16,” for your pleasure:

VELOUR

December 16

Morning

After dropping Vesta off at school, Velour approaches the house like a cloud, vaporous and without essence—blank, barely moving. In the car, the child ran her mouth while double fisting waffles in the front seat and insisting that Velour pay extra special attention to Franz today, giving him love, because he apparently had nightmares. Vesta claimed the dog was kicking and crying in bed. Velour promised. But, she doesn’t remember driving home, doesn’t even know she’s walking towards the door and that the door belongs to her house. She’s recalling a conversation she’d overheard between her mother and Todd, one of the curators at the NAT Museum, last night. Vivienne’s end went something like:

I won’t

How should I know

I’m not a therapist

Wanting to include

Sure

Fine

A warning

No

No

No

Absolutely

No

Yes

I understand

The machine

I do not think

May I finish?

Would object to my being in the same show

There are many reasons I stopped

Among them, the creation of art, especially with the intention of showing to a public

Was not good for my character

Sure

Yes

Fine

By then, Hans was gone

No

Love? Amour?

Mais bien sur

Oui

Oui

I’m nearly ninety

Well, eighty-two but still

Religious

Yes

I myself don’t condone suicide

God-given life

Sure, we spoke

I told her a tale of a ribbon and a road

It was a metaphor

No

No

An interrogation

C’est impossible!

No

You’ve already made up your mind

Yes

Okay

Right

A statement, fine

Online

Keep the works for now

I haven’t seen them in years

And I don’t want to see them now

Fine

Fine

Yes

They’re at rest

Resting

With all due respect

Oh

Would have been

Yes

Some grace

Goodbye

Velour stumbles into the kitchen, tosses the metal wad of keys onto the table, sits in her husband’s chair, and opens her laptop. As she reads the NAT’s statement, declaring that they’ve removed Vivienne from the upcoming show, guilt needles her sides. She hadn’t been listening to Vesta at all. The girl had said they were making something in school that day—something she was quite excited about, but Velour can’t recall what or why—and Vesta had provided instructions—something about love, the dog, nightmares—what? He’s over there—curled in a lopsided ball, looking half-traumatized. Velour chucks a wafle at his head. He flips it over with his nose, nudges it away, then slurps it up as though liquid.

Franz Kline was the death messenger. The dog informed Velour: your husband is gone. Franz never cared about Velour, never licked or pawed her gently awake. They were suspicious of one another. At best, they coexisted. In truth, Velour found the dog ugly and smug, his splotchy hair and skinny legs, brown with stripes of warm black and a red undertone which makes him look, in this winter light, like an oily otter. She eyes the tired creature, lighting a cigarette, thinking back to that other December morning, when Franz pressed his cold wet nose against the back of her sleeping hand, waking her up. As she walked downstairs, Velour sensed the end.

Why hadn’t Franz intervened? Velour had heard stories of dogs rescuing humans from varieties of danger. If Franz had only been a better, smarter dog . . . her mind wanders into the white clouds around the house as the snow melts. She lies down on the floor beside him. What are you looking at? she whispers, as the dog, who looks ferocious up-close, smooshes his face against hers. Stunned at the sudden affection, she springs to her feet, nearly collapsing.

Velour goes upstairs to check on Vivienne, whom she hasn’t seen all morning. She opens the door without knocking, forgetting it’s Thursday and Lou has off. When she busts in, he’s sitting up in bed, bare chested and staring, and Vivienne’s beside him, dead asleep. There’s a tenderness that moves between their resting bodies which Velour hardens against. Curled into a small fetal ball, her mother looks like a child. Velour’s heart quickens.

-Uh. What’s up? Lou whispers.

-Just checking on you guys.

-Why?

-I had a weird . . . a weird feeling, Velour whispers. For a second, she mistakes her own voice for her daughter’s.

-One of your feelings huh?

-Shut up.

-Are you gonna keep standing there? Lou whispers.

-No. Can you go to the patriot grocery today?

-Sure. I have some shit to do in town anyway.

Vivienne stirs and Lou keeps staring at Velour in that particularly penetrating, stuporous manner. She reverses out of the room, awkward—like an animal or an alien, a notch or two away from human. Velour and Lou refer to the big store at the edge of town as the patriot grocery because they play songs about America and there’s a giant painting of a flag on the front windows. She can’t think of what they would need there, but Velour doesn’t want Lou around. She has to focus. To focus, she needs to sit in Max’s chair at the kitchen table, where she can feel her body getting enlivened by extra shots of electricity and druggy euphoria. Velour sees the chair as a power center. The other power center is the basement where they keep her father’s doll sculpture, The Machine-Gunneress in a State of Grace.

In the chair, she starts her day’s work. She begins looking through the hundreds of photos on her computer, clicking on images of her mother’s drawings and sculptures and life while occasionally flashing to Max, his skinny body slumped over the white farm table. Velour herself had never shot up. Perhaps, she thinks, looking at the pictures, her aversion to needles has something to do with growing up around tools for sewing and seam ripping, instruments which change the form of anything. The silvery alchemical vigor of needles—mend, kill, cure, poison, rip.

Alterations, alterations.

Thank you! This looks great, just ordered the book. 💙📚