A Note from Arcade

As promised, we have some exciting new content on the Arcade Publishing Substack.

In an effort to engage more collaboratively with various writers, creators, and readers on the platform—and in so doing, spark up more constructive and critical conversations about the state of contemporary literature and the changing role of the publishing industry—we are working more directly with writers on this platform who we admire.

Hence, we are thrilled to share an original essay by John Pistelli.

In this essay, John shares his thoughts on the evolution of literature-as-magic, and how it relates to the evolution of other art forms—and to the ineffable—with subjects ranging from our very own novelist, Bruce Wagner, to the English Romantic visionary, William Blake.

If you enjoy this essay, we encourage you to subscribe to John’s Substack: his newsletter, Weekly Readings, and his courses on literature called The Invisible College are essential for anyone attempting to integrate themselves into the online literary discourse (or to simply learn more about literature at a low price).

And, of course, subscribe to Arcade Publishing’s Newsletter for more upcoming collaborations, including updates and reminders about the Arcade Publishing reading on February 21st.

Literature and Magic: The Marriage of Word and Image

By John Pistelli

Is literature the same as writing? The historian would say “yes.” Out of the song cycles and ritual performances of an oral culture, the discriminated genres of poetry and prose—epic, dramatic, lyric—accompanied the development of a literate culture. With the growth of print out of literate culture in the last millennium came the literature we know: verbal arts and entertainments, the novel chief among them, bound in printed books and marked for sale.

Whatever “literature” was before writing and before print, it was not a special use of language set aside from workaday communication for the purposes of diversion, as it is for us. Literature was incantation and propitiation, a traffic with the divine, akin to the bison painted on the cave wall before the hunt or the dance in imitation of the stars in their courses: in short, magic. But we hear a hint of the sacred still clinging to the idea that literature is a use of language “set aside” from the quotidian and the mundane.

The modern literary artists who most wanted to restore literature to magic—to free it from mere writing—did so by trying to reunite the word to the image, to the song, and to the dance, by rejoining the sundered media in a new marriage of word, spectacle and performance.

Marshall McLuhan famously distinguished between cool and hot media: cool media is a fragmentary, low-resolution, and low-information form that requires audience collaboration to consummate itself (e.g., woodblock prints, the comic book, television); hot media, by contrast, are much more high-resolution and therefore require less work from the audience, whether the medium is writing and print, with their orderly exposition, or radio, with its hypnotic tribal rhythm.

To restore literature to magic, to free it from writing, poets and novelists lower it from hot to cool: from serried sentences delivering information to a passive reader to a more delirious dance of lexis and syntax the participatory reader is invited to join. Less well-known than McLuhan’s canonical hot/cool distinction is his observation, in Understanding Media, that the modernists, under the influence of late-19th-century electric-age innovations in media such as the telegraph and newspaper, began this cooling process:

The format of the press—that is, its structural characteristics—were quite naturally taken over by the poets after Baudelaire in order to evoke an inclusive awareness. Our ordinary newspaper page today is not only symbolist and surrealist in an avant-garde way, but it was the earlier inspiration of symbolism and surrealism in art and poetry, as anybody can discover by reading Flaubert or Rimbaud. Approached as newspaper form, any part of Joyce’s Ulysses or any poem of T. S. Eliot’s before the Quartets is more readily enjoyed. Such, however, is the austere continuity of book culture that it scorns to notice these liaisons dangereuses among the media, especially the scandalous affairs of the book-page with electronic creatures from the other side of the linotype.

We could multiply examples in both elite and mass culture of such dangerous liaisons. For example, in his McLuhanesque Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud tasks the medium he calls “sequential art,” developed in its modern form in the newspaper funny pages at the same turn-of-the-century moment as modernism itself, with healing the rift in the western psyche between intellect and experience, which he identifies with word and image, respectively. Nick Sousanis’s later comic-book treatise Unflattening, the first doctoral dissertation produced in comics form, makes explicit the idea that comics can rejoin our left and right brains.

Also contemporary with modernism is Richard Wagner’s theory of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total artwork: the Wagnerian opera would not only represent the fusion of all the arts into one supra-art—music, poetry, painting, song, dance, costume, architecture, and more—but would also unite the new German nation around the totalized stage. Wagner’s legacy is mixed. His ideas not only influenced such progressive avant-gardists as the Bauhaus movement in their ambition to revolutionize everyday life but were arguably best fulfilled in and by cinema. Still, we tend to take his example as a cautionary one given its influence on the Nazis. Black magic: like a sorcerer’s apprentice summoning forces beyond his control, the total artwork conjures the total state, which subjugates the people in turn, not excluding the censored or slaughtered “degenerate artists” among them.

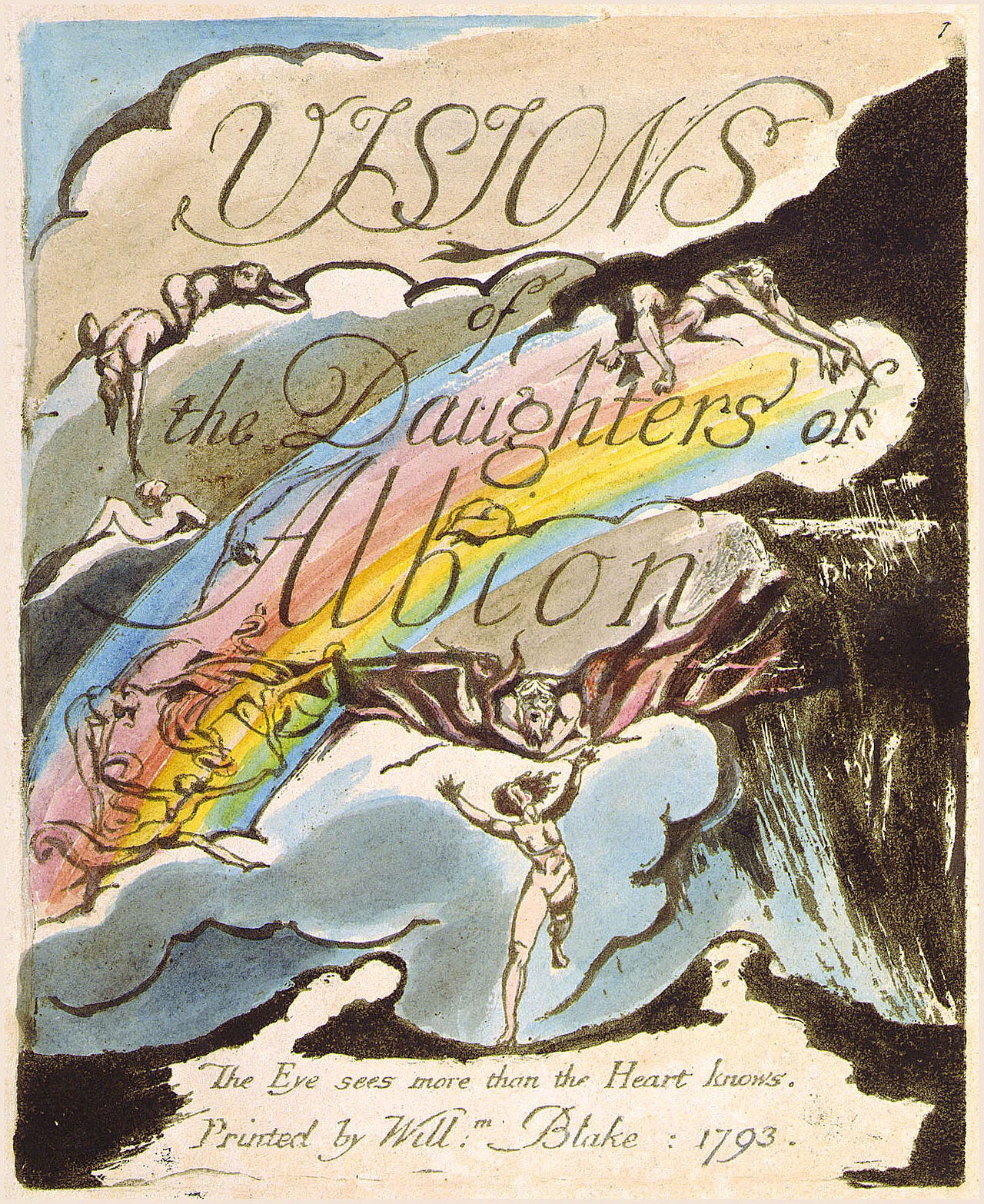

Both the desire and the danger to raise literature to the level of total artwork pre-date modernism and McLuhan’s electric age. At the revolutionary dawn of Romanticism at the turn of the 19th century, William Blake’s self-engraved epic poems combined word and image into an almost unreadable wall of text representing the poet’s private mythology of a world transfigured and redeemed by imagination. For his labors, largely unrewarded in his own time, Blake has been called the first graphic novelist.

As his academic exegete Northrop Frye reveals in Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake, however, the poet, toward the end of his life, was planning a Gesamtkunstwerk of his own: an overthrow of private easel painting in oils and a revival of public fresco painting, accompanied by his own pedagogical writings and poems meant to revive the moribund, reactionary nation. Otherwise sympathetic to Blake, Frye, writing just after World War II, points out the danger in such an ambition:

But a cultural leader bent on reviving dramatic art in such a milieu, whether in music, drama or fresco, would have to be a very different kind of man. He would have to give the public what would appeal not only to their sense of community but to their sense of herded solidarity; that is, he would have to appeal to both the best and the worst tendencies of his nation, and would therefore himself have to be both genius and megalomaniac. As a genius he would visualize great things, and as a megalomaniac he would carry them out in the teeth of frantic opposition. As a genius he would give his nation its archetypal vision, but his achievement would be too egocentric to leave an integrated tradition behind. But Blake was not Wagner, nor was England Germany. […] But Blake’s willingness to become a public leader of art shows a confusion in his mind between two things which are carefully distinguished in [his] Prophecies: the imagination and the will…the struggle of art to perfect its vision and the attempt of the will to alter the world of experience.

Blake, Wagner, and McLuhan dreamed of a mass art, no matter how participatory in theory. Poem or painting, comic book or TV broadcast: in the 19th and 20th century, they all went out from a central point of dissemination to an audience unable to reply on the same channel. Obviously, our online world enables much more two-way cultural traffic; writer and reader, viewer and performer, change roles from hour to hour, from minute to minute. The online Gesamtkunstwerk is not so much what any one creator produces but is rather the totality of the timeline. As art theorist Boris Groys argues in his On the Flow, we really have restored the making of art to magical ritual, inasmuch as we now perform less for each other than for whatever god is the only conceivable entity able to “read” the whole internet.

In these circumstances, literature mingles promiscuously on the timeline with visual images of all kinds, videos from the animated to the documented, all manner of music and performance, and even media generated by artificial intelligence, proving the point with which we began: to be freed from mere writing, to return to magic, literature must rejoin the other media. The lack of overt top-down mass coordination of media, the fascist potential that deformed Wagner’s project, renders the contemporary Gesamtkunstwerk less dangerous than the modern one, notwithstanding the self-interested interference of tech barons (and their government allies) in the platforms they oversee.

It remains to be seen whether and how much this mingling of media will influence the print book, a technology too durable and economical, not to mention aesthetically pleasing, ever to abandon. Over a decade ago, novelist Tim Parks looked forward, in an essay in the New York Review of Books, to the ebook’s purification of literature:

The e-book, by eliminating all variations in the appearance and weight of the material object we hold in our hand and by discouraging anything but our focus on where we are in the sequence of words (the page once read disappears, the page to come has yet to appear) would seem to bring us closer than the paper book to the essence of the literary experience. Certainly it offers a more austere, direct engagement with the words appearing before us and disappearing behind us than the traditional paper book offers, giving no fetishistic gratification as we cover our walls with famous names. It is as if one had been freed from everything extraneous and distracting surrounding the text to focus on the pleasure of the words themselves. In this sense the passage from paper to e-book is not unlike the moment when we passed from illustrated children’s books to the adult version of the page that is only text. This is a medium for grown-ups.

This prophecy proved premature, both because the ebook has failed to make the obdurate print book obsolete and because online writing has, if anything, “regressed” to what Parks would see as the “childish” world of images.

Parks’s longing for purification sits at the other pole of modernism from the Joycean maximalism that would, following Blake and Wagner, turn text into image and song. Joyce’s rebellious disciple Beckett might be the best example of such word-purity in his intense verbal minimalism—except that he, no less than Wagner, took his poetry to the performance space. Likewise, such Beckettian late-modernist progeny in more recent days as W. G. Sebald, with his novels-incorporating-photography, or Karl Ove Knausgaard, with his work’s intense engagement with painting, can’t achieve the desired “essence of the literary experience” any more than their master could.

Purity is the most impossible of all longings. The novel may in consequence always liaise with the graphic novel. My own forthcoming novel, Major Arcana, about a magician and comic-book writer, is about this very inevitability.

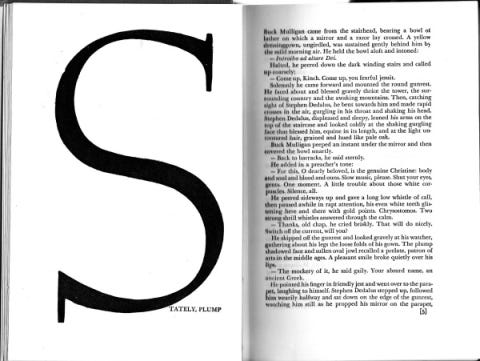

As this essay appears under the auspices of the admirably freethinking Arcade Publishing—founded by Richard Seaver, as it happens, who could be said to have “discovered” Beckett—I will advert in conclusion to one of its own current authors, Bruce Wagner. (No relation, I assume, to the aforementioned operameister.) For Wagner, an L.A. native screenwriter-turned-novelist who writes almost obsessively of Hollywood, the mixing of media comes naturally. Wagner has spoken of being inspired at the beginning of his literary life by the giant page-tall capital “S” in “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan” that famously inaugurates the Random House edition of Joyce’s Ulysses, a letter so outsized that it becomes a picture. Wagner’s whole project might be said to proceed, then, from the modernist desire to fuse word and image, to reunite literature with the other arts.

Accordingly, the use of online discourse from comments sections to hashtags to clickbait headlines in many of Wagner’s novels from 2012’s Dead Stars forward is more than a timely gimmick; if these novels use online media to break literature free from mere writing, they also transfigure online media, crass and brutal and superficial as it often is, to literature’s “artifice of eternity.”

Wagner and his book-designing collaborators have sought more subtle effects as well. To a reader first opening his 2022 novel ROAR: American Master, The Oral Biography of Roger Orr and seeing Winslow Homer’s painting Summer Night reproduced on the endpapers of the hardcover, the use of the image may seem only a pleasing artistic flourish. The reader who has finished the epic narrative, however, and learned the role the painting plays in it and what it represents to the characters, the art is no longer decorative but fully significant; no one who sees the painting in another context will do so without thinking of Wagner’s magisterial family saga. This is cool media—the image-word juxtaposition requiring reader agency to interpret—at its best.

Another Arcade author,

, achieves a similar magic trick in her 2024 novel Vivienne, which annexes the work of Surrealist sculptor Hans Bellmer—as well as online discourse—to a family saga as funny and moving as Wagner’s.These canny uses of the image to enhance the word are a far cry from contemporary mainstream publishing’s banal visual homogenization of fiction into what has aptly been called “the book blob,” the design corollary to what is too often corporate novels’ sameness of style and subject matter.

Our online lives have brought us many curses and blessings, and we tend to focus on the former, from pervasive self-commodification and atomization to an intensely fractious public sphere. Among the blessings, however, are continued reminders of literature’s ability to transcend writing and its linear messages, to rejoin the other arts in a performance meant to communicate with the ineffable and alter the real. In our newest innovations we find our oldest impulses—and literature becomes magic again.

“Arcade is a storied literary imprint (its original publisher discovered Samuel Beckett) that mirrors and embodies Tony Lyons’s fierce, lifelong commitment to writers and their art. After thirty-five years and fourteen novels, I have never been treated with more care, respect, and devotion, and have never, hands-down, had such beautiful books created from my work than with Arcade . . . Long may Arcade (and Tony Lyons) live!”

—BRUCE WAGNER