A Note from Arcade

The perceived moral and societal duties of publishers is a topic covered frequently in contemporary literary discourse, but not so often in a religious framework: the writer-as-worshiper, for many, disappeared perhaps as early as the Enlightenment. So, here to reintroduce a religious component of writing that is perhaps implicit in the act of writing itself—and thus the act of publishing as an economic endeavor—is the cultural commentator and urban theologian Stephen Adubato.

Be sure to check out Stephen’s magazine, Cracks in Postmodernity (here on Substack and in print), which frequently delves into such culturally- and politically-charged themes within the framework of contemporary religiosity.

This is a truly original, personal, and insightful contemplation on the act of writing, so please do enjoy.

Nepobabies Revisited: An Apologia

By Stephen Adubato

Upon walking into my family’s beachfront vacation home, I checked my bags, which were full of books by Kierkegaard, Paglia, Lasch, Girard, Huysmans, Teresa of Avila, and Dorothy Day; full of exquisite, exotic treats from the Lebanese bakery down the block from me in Brooklyn, honey from the farmer’s market, fresh feta dripping with brine, loose-leaf Earl Gray, lavender flowers, and ingredients to make a Greek bean dish whose flavor is perplexingly robust and satisfying; full of my laptop, rosary, American Spirits, several witty graphic tees created by crafty Etsy shops, sweatpants and sweatshirts—but not my privilege—at the door. My armory of supplies would sustain me in my noble battle: to hammer out the proposal for the book I hoped (yearned, prayed) someone would publish—my privilege, perhaps, being my most powerful (and necessary) weapon.

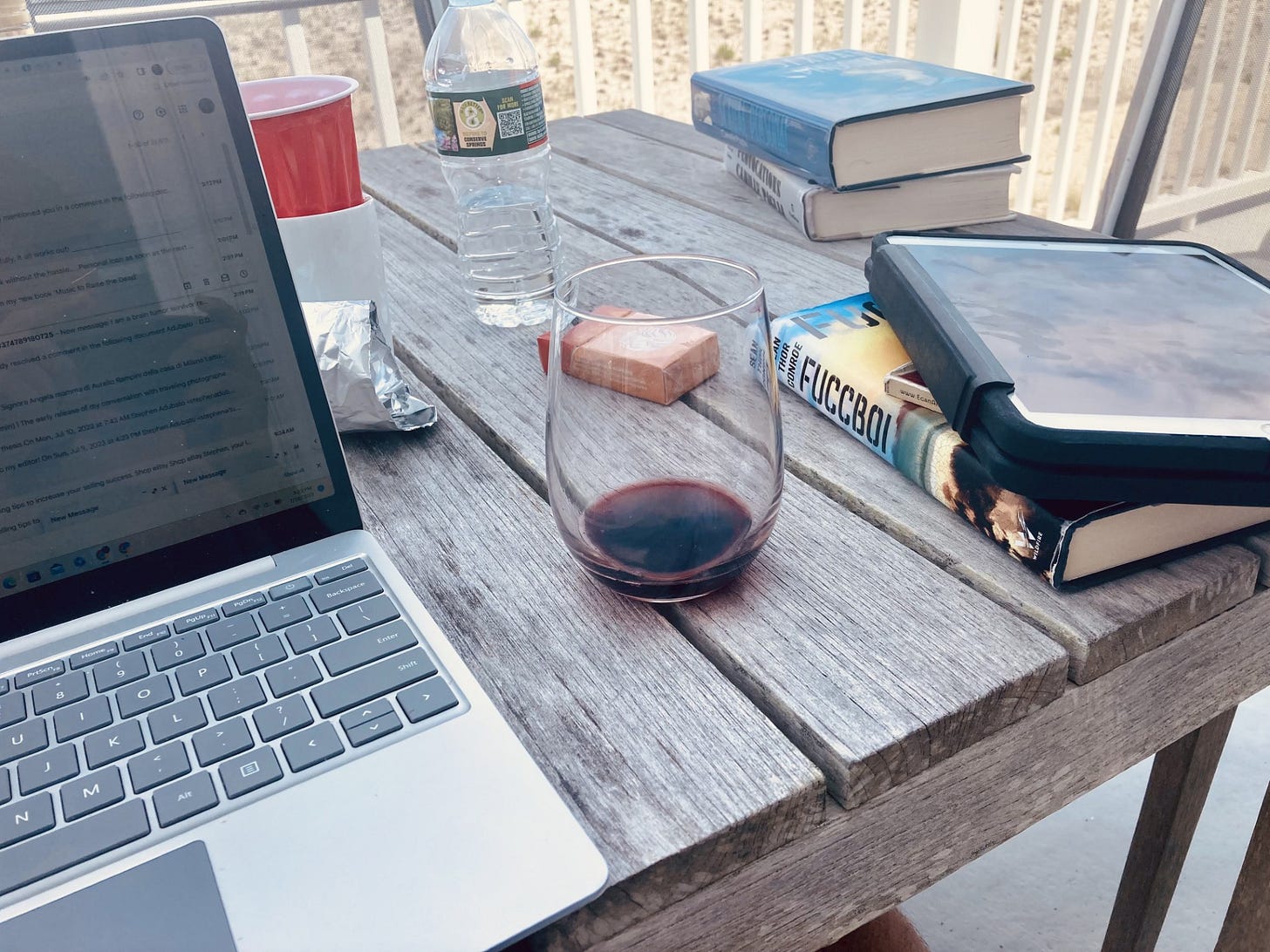

I dumped a generous amount of the tea leaves into a white porcelain pot and rolled the lavender flowers between my fingers and dropped them in—pausing to sniff the luxuriant aroma on my fingers—and poured the boiling water over them, watching the coils of smoke dance in the sun streaming through the windows of the French door overlooking the sea. I placed it on a tray with wild flowers painted on it that a relative brought back from England, covered the pot with the top and draped a dishrag over it to keep the heat in. I unwrapped one of the pistachio and rose water-filled ma’amoul and placed it on a Villeroy & Boch saucer next to the pot along with my matchbook and Spirits, and carried it out to the deck. I lit up a cig and smoked it while watching the waves of the Atlantic crash against the shore, waiting patiently for the leaves to fully unfurl into the water so it could absorb the entirety of the flavor they possessed inside them, and cracked open my copy of Day’s collected newspaper clippings.

We must talk about poverty, because people insulated by their own comfort lose sight of it . . . We must keep on talking about voluntary poverty, and holy poverty, because it is only if we can consent to strip ourselves that we can put on Christ. It is only if we love poverty that we are going to have the means to help others.

I once commented to a friend that I felt like Dorothy Day while sitting out on the deck, dragging on a cig, looking out over the sea, and contemplating what I would write about. Dorothy also went to her shore house with several packs of ciggies when she wanted to get away and write. But reading this passage from her 1945 article on voluntary poverty reminded me of the perverse irony of my comment: Dorothy’s shore house on Staten Island was more of a shack, unlike my family’s place with its numerous bedrooms, electric fireplace, and speakers built into the ceilings.

Given Day’s meager budget, it’s not very likely that she could afford to be a connoisseur of fine cookies and tea like myself. I doubt she would scoff when reading the ingredients on the label whenever shortening, vanillin, or high-fructose corn syrup appeared, as I do. I doubt that she indulged in watching loose-leaf tea leaves unleash their flavor into the water, especially not when she was preparing to feed hundreds of hungry folk waiting on the soup line outside the Catholic Worker on the Lower East Side, as she probably only had the time, energy, and funds to sip from a cup with a bargain brand tea bag in it—the lack of comfort it provided perhaps being a motivator to set out and get to work and serve, whereas I’d be likely to complain without end were I forced to guzzle a nasty cup of Lipton (or worse, Tetley) on-the-go, using it as an excuse as to why I was unable to get any work done.

While I’m already flagellating myself for my peccadilloes, I may as well own up to the fact that my greatest “privilege” is probably not that of having a family with a shore house where I consume luxurious snacks, but rather that of getting to dedicate such a significant portion of my time to thinking and writing about useless things. The sociologist Musa al-Gharbi recently wrote that:

Similar to academia, newsrooms have come to increasingly rely on poorly compensated (or altogether uncompensated) labor. Freelancers are typically paid little to nothing because the pool of people desperate to have their work published anywhere (especially prestige media outlets) has grown so large. But of course, it is a very particular type of young person who can work long and flexible hours without getting paid (or barely getting paid), yet still survive in the expensive cities that media organizations are located in: people who come from wealthy backgrounds…Consequently, journalism’s increased reliance on freelancers and interns has reinforced and accelerated its transformation into a profession of privilege.1

The association of the vocation of writing with aristocratic systems and values is not exactly new. Needless to say, those who are born into more comfortable circumstances have easier access to the time, resources, and mental space required to write. And while there are plenty of brilliant writers who came from a struggle, their having to churn out ingenious masterpieces while living the life of a starving artist scraping just enough to get by looks—and feels—quite different from the lives of writers born into the so-called “leisure class.” Day herself pumped out countless books and articles, usually doing so in poorly heated and bug-infested shelters—a far cry from a lavish beach house.

I can’t blame my friend for giving me a hard side eye after proclaiming my affinity with Dorothy Day. It would be hard for me to argue that my more-often-than-not playful—bordering on decadent—musings about religion, philosophy, and pop culture are anywhere on par with Dorothy’s dedication to improving our society. As much as I can’t expect anyone to let me off the hook of my own cognitive dissonance, I’d insist that the matter of the “usefulness” of one’s contribution to society deserves further consideration.

Someone’s Gotta Do It

Perhaps the best case for leaning into—rather than renouncing—one’s privileges is the notion that contemplating and writing about the “great ideas” and other useless topics is a public service. In her commentary on Rene Girard’s Deceit, Desire, and the Novel, A. Natasha Joukovsky writes that those with certain “aristocratic” comforts can choose to use their privilege to explore certain metaphysical ideals that, while pertaining to all of us, many do not have the resources to explore in depth.

This harkens back to the feudalistic understanding that each social class had a responsibility to each other: Whether one was called to govern the nation, to defend it in battle, to minister to the people’s spiritual needs, to produce goods and food for all to consume, each class provided a fundamental service to the others. Even in our post-feudalistic, egalitarian world, not everyone is cut out to be a philosopher, nor is everyone cut out to be a welder. But as Mike Rowe once argued, “What we need is more welders who can discuss Kant and Descartes, and we need more philosophers who can run an even bead and repair a leaky faucet.” Thus, those who have the means to dedicate themselves to “useless” pursuits ought to do so—and should aspire to share the fruits of their labor with those who have less time to.2

The fact that people like Kierkegaard had the time and energy to dwell on his existential angst and write neurotic tomes about it is a testament to the fact that he had few material concerns with which to occupy his time. One could argue that those with “real problems” have little interest in such thoughts about the meaninglessness of existence. Perhaps Kierkegaard’s time would’ve been better spent doing something “useful.” Yet while the obsessive tone of his neurotic musings may be foreign to less bourgeois readers, his bold confrontation of the problem of meaning speaks to the universal longings—albeit being occluded by toil and other distractions—that plague all who have a soul, which is to say all human beings.

Thus, the philosopher, the novelist, the monastic, and others who think and write about “useless” things play a prophetic role, using their time to give voice to things that speak to everyone. Joukovsky goes on to quote Margaret Atwood who, despite being popularly lauded for her socially-conscious writing, asserts that the true mission of the writer is to fascinate her readers: “People are always coming up with new theories of the novel, but the main rule is: hold my attention.”

“Novels can only influence the real world if they captivate,” says Joukovsky, “and beauty is the necessary and sufficient condition to captivation.” Confronting social problems may certainly be useful, noble to a certain extent, but the true service of writing is to fascinate, to provoke, and even to entertain. Leisurely time can dispose one to contemplate profound ideas, but also to enjoyment. Joukovsky also cites writers like Wilde whose playfulness often drew boisterous laughter and merriment from readers. In his own words, “The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely. All art is quite useless.”

Aristocratic Vice: Snobbery and Virtue Signaling

Of course, Wilde’s playfulness was a double-edged sword. His more decadent works (and lifestyle) point to the flipside of the virtues of metaphysical idealism: what Girard named the aristocratic vice of snobbery. Those who have the time to contemplate such ideals can easily lose sight of their social duty and turn to self-indulgence. Joukovsky writes that “the snob mistakes society for heaven” and rather than channeling her metaphysical desire toward contemplating Being, attempts to make herself into a supreme being, a god of her own. The snob in turn, according to Girard, “desires nothingness.” There is something nihilistic about her self-indulgence, which may call to mind some recent works of autofiction, which in its excessive forms veer toward the vapid and masturbatory.

For Wilde, style and form are “absolutely essential,” so much so they become ideals in themselves rather than signs pointing to a greater ideal. Camille Paglia writes that Wilde’s aestheticism in comedies like The Importance of Being Earnest makes a pagan idol of sorts out of “the ceremony of social form.” The play “is inspired by the glamour of aristocracy alone, divorced from social function.”3 For Wilde, she continues, “no collective benefits flow from throne or court, where the upper class is at perpetual play.” He “makes aristocratic style the supreme embodiment of life as art” and “seeks out the crystallized idea or Platonic form of aristocracy . . . Language and ceremony unite to take hierarchy to its farthest dazzling point, until it becomes form without content, like the lacy latticework of a snowflake.” Of the writers of his era, she concludes, “Wilde is the most guilty of snobbery.”

Upon finding out that I have family members who own a second home, one friend scoffed with disdain. I briefly considered taking this as a provocation to renounce my privilege . . . to not only dedicate my time to endeavors that are more explicitly “useful” for society, but perhaps even to attempt to convince my more well-to-do relatives to follow Jesus’s exhortation to the rich young man and sell all their possessions and give them to the poor. Yet as much as there might be something praiseworthy about such a pivot, it’s hard to deny that many who do so—especially those who very publicly check their privilege at the door—are subconsciously driven by a narcissistic attempt to soothe their conscience.

“There’s this sense in the contemporary literary zeitgeist that novels are supposed to be these self-serious, moralistic tools for medicinal instruction,” says Joukovsky. “When the raison d’être of a novel is to signal the author’s real-world virtue, this cannot help but become visible to its readers.” Writing that focuses too heavily on social issues risks “disrupting not only the immersive experience of fiction but the very effects of mimesis that mandates like ‘acknowledge the pandemic,’ seem designed to protect . . . The great irony,” she continues, of treating literature like a “moral-medicine” is that it “largely comes from an egoic place. Specifically: the queasy sense that if art is not useful then it is a luxury—a privilege—and artists themselves an unflatteringly élite part of the political problem.”

For Joukovsky, “the place of morality in art has to be one from an observational perspective rather than a persuasive perspective . . . when the goal is transparently instructive,” one’s writing quickly morphs into propaganda, rather than allowing the observations the writer explores in her writing to provoke thought about moral ideals “organically.” Those who have the leisure to observe, to contemplate, to play, can indeed be inspired to produce works of self-indulgent snobbery, but they can also be inspired to write beautiful, fascinating, and entertaining works that uplift the souls of their readers—regardless of their socioeconomic class. Resolving to renounce one’s privilege and to only dedicate one’s time to “useful” endeavors is something of a copout from confronting this drama.

Either fully renounce and stop virtue signaling to indulge your fragile ego. Get to work serving. Live true poverty.

Or own your priv and use it for noble ends.

Don’t be a snob. Don’t be a signaler.

The Primacy of the Metaphysical

As much as Dorothy Day can be lauded for the usefulness of her dedication to serving the less privileged, I’d argue that her endeavors (and writing) were so effective precisely because they were grounded in a sort of metaphysical idealism. In addition to rooting her writing and social efforts in prayer and liturgy, she made time for taking in natural vistas of the sea and the mountains, as well as for savoring beautiful art and literature (and baked goods like cinnamon buns, whenever she had the chance). This foundation gave her social activism a depth imbued with love.

Among her favorite authors was the French decadent writer Joris-Karl Huysmans, whose redemption arc from snobbish dandy to devout ascetic inspired her conversion to Catholicism. Huysmans, whose earlier work Against Nature appears in Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (and inspired Dorian’s fall into hedonism), testifies to the aforementioned drama faced by those with ample leisure time and comforts, ultimately emerging from it with his eyes and heart set on higher ideals.

As much as I may be dismissive of my peers who ever so magnanimously (and loudly) check their privilege at the door, I can’t deny how much we share in common. Alas, what is this essay other than a belabored attempt to stave off my moral guilt for my comfortable upbringing? What can I say—the vices of both snobbery and virtue signaling ensnare me, tempting me away from using my passion for writing for the sake of the common good. For this, I turn back to Day, whose sanctity I can only aspire—and pray—to emulate. My way of serving God and neighbor may not take the forms of voluntary poverty and social advocacy. I can only hope to maintain the tension—perhaps in a different form from Dorothy—between the material and the metaphysical, the responsible and the playful, hoping to God that He can put my nepobabyish proclivities to good use.

“Indeed, many who inhabit relatively low-paid roles within the symbolic professions persist in part because they prioritize symbolic capital over financial capital: they would prefer to be a freelance writer or a part-time contingent faculty member (earning an average of $3,874 per course section) rather than work as a manager at the Cheesecake Factory, or a flight attendant, or a truck driver, or a postal worker—even if they could make a bit more money, with more stable income and better benefits, doing these other jobs instead. And symbolic capitalists often have the ability to make that choice due to other advantages they possess over others. The people who occupy the really low-paid positions within the symbolic professions (working for free or nearly so) are often able to persist in these roles while living in expensive cities (rather than relocating to somewhere more affordable but less glamorous and doing something else with their lives) because they are supported in part or in full by families or partners who tend to be relatively affluent, or because they have a nest egg of their own. Symbolic capitalists generally try to ‘stick it out’ in these positions not because they lack other options but rather because they view even the unglamorous and poorly compensated work they’re doing as more valuable or meaningful than pursuing other forms of employment that might pay more in the short to medium term.”—Musa al-Gharbi, We Have Never Been Woke

This is not to say that those who aren’t born into money shouldn’t be afforded the opportunity (via scholarships, etc.) to study/write about useless things.

“The play’s characters have abnormal attitudes, reactions, and customs and embark upon sequences of apparently irrational thought, for they are a strange hierarchic race, the aristoi…In the original script, he cries, ‘Exercise! Good God! No gentleman ever takes exercise. You don’t seem to understand what a gentleman is.’ Algernon holds the Late Romantic view of the vulgar inauthenticity of action. When Jack rebukes him for ‘calmly eating muffins’ during a crisis, he replies, ‘Well, I can’t eat muffins in an agitated manner. The butter would probably get on my cuffs.’ Muffin-eating is the only action he is guilty of. Energy is merely agitation, a Dionysian centrifuge spraying butter about the room, besmirching the burnished world of surfaces. Jack can also be epicene: he finds both town and country life ‘excessively boring’; he accepts Lady Bracknell’s definition of his smoking as a worthy full time ‘occupation’ . . . Gwendolen, with Decadent erudition, dismisses as ‘metaphysical speculation’ Jack’s plaintive question about whether she would continue to love him if his name turned out not to be Ernest. She later remarks, ‘The simplicity of your character makes you exquisitely incomprehensible to me.’ ”—Camille Paglia, Sexual Personae